The key to urban archaeology isn’t just distinguishing Roman from Victorian; it’s about reading the story of their chaotic, often destructive, interaction.

- Urban stratigraphy is read like a manuscript, where newer layers (Victorian) are built directly on, and often disturb, older ones (Roman).

- Rescue digs during modern construction are critical, revealing how one era’s infrastructure violently intersects with another’s.

- Understanding these layers involves forensic analysis of everything from soil chemistry to hidden industrial hazards like asbestos and anthrax.

Recommendation: To truly understand a city’s history, look beyond individual artifacts and learn to see the dialogue and conflict between its buried layers.

The roar of a jackhammer on a city street is the sound of the present rewriting the past. But what happens when the drill bit hits not bedrock, but a meticulously engineered Roman wall? For an urban archaeologist, this isn’t an obstacle; it’s the opening of a new chapter in a city’s ancient manuscript. Cities like London or York are not static places; they are palimpsests, documents where stories have been written, erased, and rewritten for millennia. The common understanding is that archaeologists dig down through layers, with the deepest being the oldest. But this simple view misses the drama.

The real challenge isn’t just separating a Victorian sewer pipe from a Roman hypocaust system. It’s about reading the interface layer—the zone of conflict and adaptation where one era’s progress was built on the bones of another. This is where we see the dialogue between different ages: the pragmatic Victorian engineer cutting through a Roman mosaic, the medieval builder reusing Roman stones, or the modern skyscraper foundation threatening to obliterate both. This process goes beyond simple identification; it requires a kind of archaeological forensics to decode the subtle clues left by technology, public health crises, and even decay.

This article moves beyond the simple idea of stratigraphy. We will explore how archaeologists read the complex and often violent narrative of the urban underground. We will examine what happens when modern construction collides with ancient history, compare the grand engineering of different eras, and see how the past can be both preserved and presented in the heart of a bustling metropolis. Finally, we’ll look at the hidden dangers and the meticulous processes required to understand and protect this fragile heritage continuum.

This guide delves into the specific methods and mindsets required to decipher these layered histories. Below is a summary of the key areas we will explore to understand how the story of a city is pieced together from the fragments beneath our feet.

Contents: Decoding the Layers of Urban History

- Reading the Dirt: How Do You Know Which Layer is Roman and Which is Medieval?

- The Rescue Dig: What Happens When a Skyscraper Foundation Hits a Roman Wall?

- Aqueducts vs Sewers: Who Managed Public Health Better, Romans or Victorians?

- Glass Floors: Is Leaving Ruins Visible Under Buildings a Good Idea?

- Pottery Shards: How to Make Broken Ceramics Interesting to School Kids?

- Rotting Floors and Asbestos: How to Spot Invisible Hazards in Derelict Mills?

- The Lost-Wax Process: Why Does It Take 3 Months to Cast One Figure?

- How Mass Tourism Erodes the Physical Fabric of Heritage Sites?

Reading the Dirt: How Do You Know Which Layer is Roman and Which is Medieval?

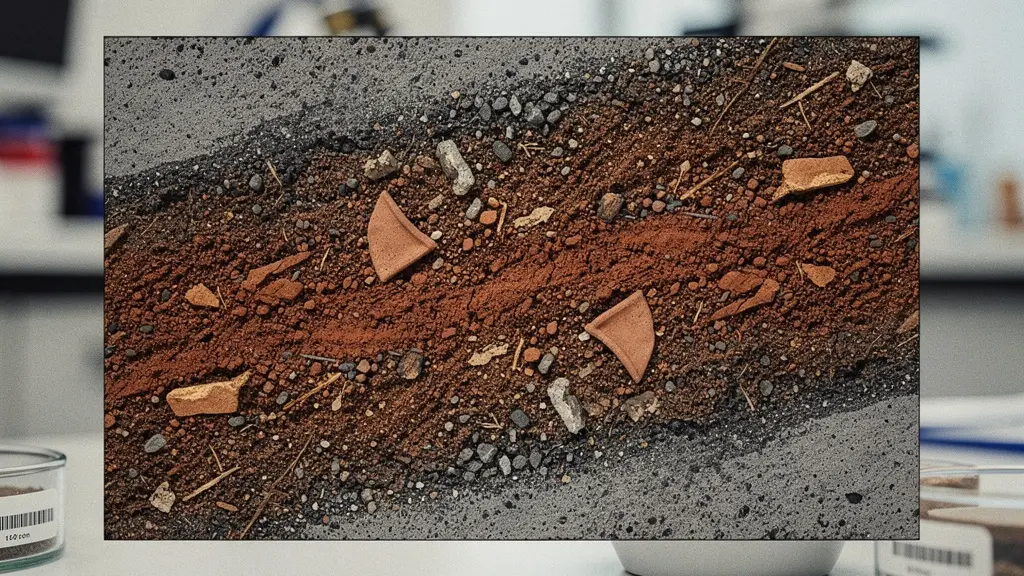

The fundamental principle of excavation is stratigraphy: the idea that soil and debris accumulate in layers, with the newest on top. But in a dense urban environment, this is rarely a neat stack of pancakes. Layers are sloped, cut into, and disturbed by everything from rubbish pits to burials. An archaeologist doesn’t just dig down; they read the dirt. The colour, texture, and composition of the soil are clues. A dark, organic-rich layer might signify a garden or dump, while a layer of charcoal and burnt clay could be the dramatic signature of a fire, like the one that destroyed Roman Londinium.

To make sense of this chaos, we use tools like the Harris Matrix, a diagramming method that maps the temporal relationships between every deposit, wall, and pit. The key is finding datable artifacts. A coin provides a ‘terminus post quem’ or “date after which” the layer must have been deposited. But what if there are no coins? This is where scientific techniques come in. The Sweet Track in Somerset, an ancient wooden trackway, was precisely dated using dendrochronology (tree-ring dating). In urban contexts, we might use micromorphology—the microscopic analysis of soil composition—to identify markers of human activity. In fact, recent micromorphological studies demonstrate an 85% accuracy rate in dating layers even without artifacts.

Case Study: Sweet Track Precision Dating

The Sweet Track in Somerset, an ancient wooden trackway, was precisely dated to 3807 BCE using dendrochronology combined with stratigraphic analysis. This case demonstrates how multiple dating methods can provide exact calendar dates for prehistoric structures, a principle applied in more complex urban settings to differentiate between eras like Roman and medieval when clear markers are absent.

Ultimately, separating Roman from Victorian is a process of assembling multiple lines of evidence—the style of masonry, the type of mortar, the fragments of pottery, and the very story the soil tells—to build a coherent timeline from a disturbed and complex urban manuscript.

The Rescue Dig: What Happens When a Skyscraper Foundation Hits a Roman Wall?

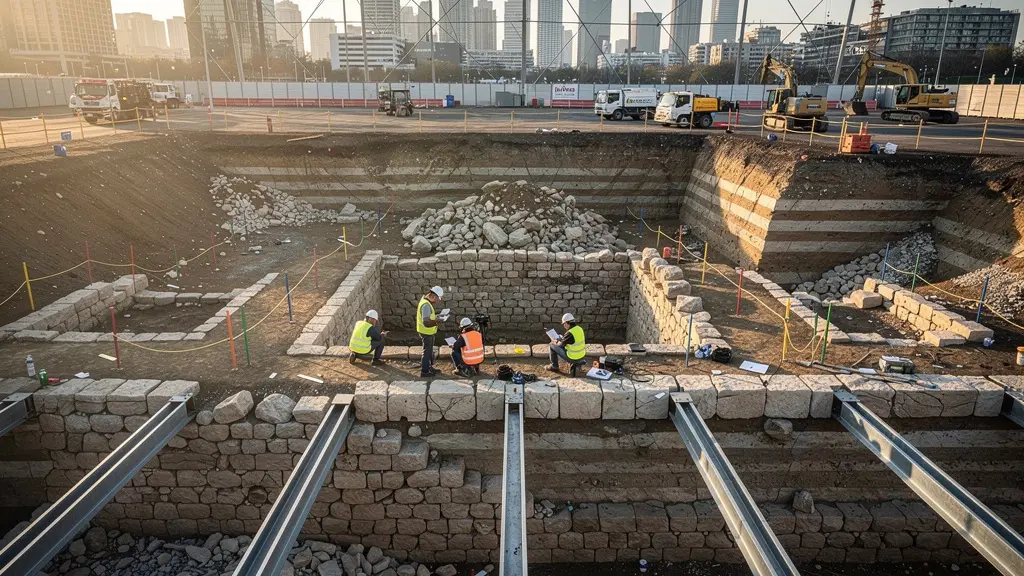

In the UK, the past is a formal part of the planning process. Before a single pile is driven for a new skyscraper, developers are often required to fund an archaeological evaluation. This is the world of planning-led archaeology, where the clock is always ticking. When foundations encounter something significant, like a Roman wall or a Saxon burial, it triggers a ‘rescue dig’. This isn’t a leisurely academic excavation; it’s a high-pressure, meticulously documented operation to record and recover as much information as possible before construction proceeds.

The goal is preservation by record. While physical preservation in-situ is ideal, it’s not always feasible. The team’s job is to create a complete digital and paper archive so that even if the structure is removed, its data is saved for future study. This process is far less disruptive than many assume. As Tim Malim, a leader in the field, points out, collaboration is key.

Disruption to construction should not occur if the proper advice is taken and archaeology is integrated as part of a carefully planned approach towards project delivery

– Tim Malim, Technical Director for Archaeology and Heritage, Chair of FAME

Furthermore, the financial impact is often minimal. Contrary to the belief that archaeology cripples projects, rigorous analysis has shown its cost-effectiveness. In fact, research indicates that archaeological work accounts for less than 0.2% of total construction costs in most cases, a small price for safeguarding millennia of history. A watching brief, where an archaeologist monitors groundwork, is often all that is required.

The rescue dig is the front line of urban archaeology, a pragmatic compromise between development and heritage that ensures the story of the city’s past is not lost to the relentless pace of its future.

Aqueducts vs Sewers: Who Managed Public Health Better, Romans or Victorians?

The material dialogue between Roman and Victorian engineering is most evident in their management of water. Both eras were defined by massive public works projects, but their philosophies and technologies differed profoundly, with lasting impacts on public health. The Romans engineered systems based on continuous flow, using gravity to bring fresh water in via aqueducts and flush waste out through channels like the famous Cloaca Maxima in Rome. Their use of lead pipes and waterproof opus signinum concrete was revolutionary, but it also introduced risks like low-level lead exposure. Across London, for example, excavations consistently reveal a distinct burnt layer dating to AD 60. This is the Boudican destruction layer, a crucial chronological marker separating early Roman from later Imperial periods, and the infrastructure before and after this event shows a clear evolution in design.

| Aspect | Roman System | Victorian System |

|---|---|---|

| Water Flow Method | Continuous gravity-fed flow | Pressurized pipe systems |

| Primary Material | Lead pipes, opus signinum concrete | Cast iron, ceramic pipes |

| Waste Management | Flowing water removal via Cloaca Maxima | Combined sewer systems |

| Public Health Impact | Low-level lead exposure | Great Stink of 1858 from design flaws |

The Victorians, facing industrial-scale urban populations, developed pressurized systems using cast iron and ceramic pipes. Joseph Bazalgette’s London sewer system was a monumental achievement, designed in response to “The Great Stink” of 1858 when the Thames became an open sewer. However, their combined sewer design, which mixed rainwater with sewage, is a legacy that modern cities still grapple with during heavy rainfall, leading to overflows. While the Victorians solved the immediate cholera crisis, their system had its own long-term flaws. Neither system was perfect, but both represent incredible engineering feats that fundamentally shaped the health and structure of their respective cities.

When an archaeologist uncovers a Roman drain beneath a Victorian sewer, they are not just finding two pipes; they are finding two different solutions to the timeless urban problem of sanitation, each with its own genius and its own hidden costs.

Glass Floors: Is Leaving Ruins Visible Under Buildings a Good Idea?

Once a significant ruin is discovered, the question becomes: what now? One of the most visually striking solutions is in-situ preservation, where remains are left in place and integrated into new architecture, often visible beneath a glass floor. This approach offers a powerful, direct connection to the past, transforming a basement or lobby into a museum. It celebrates the urban palimpsest, allowing modern life to coexist with ancient foundations. Examples like the Roman bathhouse at Billingsgate in London or the medieval walls beneath a hotel in York showcase this method’s potential.

However, it is not a simple solution. Exposing ruins to air, light, and fluctuating temperatures after centuries of stable burial can accelerate their decay. It requires a significant commitment to conservation, including sophisticated climate control and structural engineering. The decision to preserve in-situ must be based on a careful assessment of the remains’ significance and the feasibility of long-term maintenance. Fortunately, concerted efforts in the heritage sector are showing results, as Historic England reports 124 historic sites were saved and removed from the at-risk register in the last year, many through such proactive conservation strategies.

Checklist for In-Situ Archaeological Preservation

- Assess environmental conditions: monitor humidity, temperature, and light exposure levels continuously to establish a baseline.

- Install climate control systems: implement dedicated HVAC systems to maintain stable conditions and prevent moisture buildup or excessive drying beneath the building.

- Implement protective glass flooring: use specialized, load-bearing glass with integrated UV filtering properties to minimize light damage.

- Create maintenance access points: design discreet hatches or removable panels that allow conservators regular access for cleaning, monitoring, and treatment.

- Develop interpretation materials: install signage, digital displays, or guides explaining the ruins’ context and significance to the public.

When done correctly, displaying ruins under glass is more than an aesthetic choice; it is a declaration that the city’s history is a living part of its present, not something to be hidden or paved over.

Pottery Shards: How to Make Broken Ceramics Interesting to School Kids?

For most people, a bucket of brown, broken pottery shards is just old rubbish. For an archaeologist, it’s data. But how do you bridge that gap and make this data exciting for a group of ten-year-olds? The key is to shift the focus from the object to the story. A single shard of Samian ware isn’t just a piece of a bowl; it’s a connection to a Roman soldier eating his lunch 2,000 years ago. Its glossy red finish and place of origin in Gaul tell a story of trade, the Roman Empire’s vastness, and industrial-scale production.

Hands-on activities are transformative. Allowing children to wash, sort, and try to piece together fragments turns them into archaeological detectives. This process of experimental archaeology teaches them about form, function, and the immense puzzle of reconstruction. It’s not about completing the puzzle, but understanding the process of discovery. This philosophy was central to the success of television programs that brought archaeology to the masses.

The key to the show’s success was a focus on the process and not just the end result. What might begin as a Roman bathhouse on Day 1 could easily become a Victorian cowshed by Day 3

– Current Archaeology Magazine, Time Team Returns Feature

The goal is to ignite curiosity by revealing the narrative hidden in the fragments. By asking questions—Who made this? Who used it? How did it break? What does the decoration mean?—a simple shard becomes a tangible link to a person from the past, making history personal and deeply engaging.

Ultimately, making pottery interesting isn’t about the ceramic itself; it’s about using it as a key to unlock the human stories embedded within the dirt.

Rotting Floors and Asbestos: How to Spot Invisible Hazards in Derelict Mills?

The urban palimpsest isn’t limited to Roman and medieval layers. The industrial revolution wrote one of the most significant and hazardous chapters in Britain’s urban history. When archaeologists excavate Victorian industrial sites like textile mills or factories, they aren’t just looking for machinery foundations; they are stepping into a forensic minefield. The glamour of unearthing a Roman mosaic is replaced by the grim reality of identifying invisible threats. The work becomes less about treasure and more about safety and scientific analysis.

Hazards like asbestos, used widely for insulation, are well-known. But the dangers are often more specific and insidious. Heavy metal contamination from lead-based paints or mercury from felt-making processes can saturate the soil and brickwork. The very dust in the air can be toxic. One of the most chilling dangers is biological. As one archaeologist recounted, the past can harbor dormant but deadly threats.

Working on Victorian industrial sites requires constant vigilance. We discovered anthrax spores in a wool mill floor that had been sealed for over a century – proper hazmat protocols saved our team from serious exposure.

– Field Archaeologist, University of Liverpool

Detecting these threats requires a modern toolkit. Archaeologists use portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzers to detect heavy metal contamination on-site without destructive sampling. Drone-mounted thermal cameras can spot moisture trapped under floors, indicating structural decay. This is archaeological forensics, where understanding the industrial process that took place on a site is key to predicting the chemical and biological hazards left behind. It’s a stark reminder that every layer of history, even the more recent, has its own unique dangers.

In this context, the archaeologist’s trowel works alongside a Geiger counter and a hazmat suit, reading a chapter of urban history written in poison and decay.

The Lost-Wax Process: Why Does It Take 3 Months to Cast One Figure?

Understanding the past often requires recreating its processes. While an archaeologist’s primary job is to excavate, a crucial part of the discipline is understanding how ancient objects were made. This is the realm of experimental archaeology, and few processes are as intricate and time-consuming as ancient bronze casting using the lost-wax method. This technique, used for millennia to create everything from Roman statues to intricate brooches, serves as a powerful metaphor for the archaeological process itself: it is slow, meticulous, and multi-staged, with success dependent on a deep understanding of materials.

The process begins with an artist sculpting a figure in beeswax. This delicate original is then encased in a ceramic shell, built up in many layers over days. Once hardened, the mold is heated, the wax melts and runs out (hence “lost-wax”), leaving a hollow cavity. Molten bronze is poured in, and after a slow cooling, the ceramic shell is carefully broken away to reveal the metal figure. But the work is far from over. The rough casting requires weeks of ‘chasing work‘—filing, grinding, and polishing—to match the artist’s original vision. As recreated by projects like Time Team, the entire sequence highlights the immense skill and patience involved.

Case Study: Time Team’s Bronze Casting Recreation

Time Team’s experimental archaeology demonstrations have recreated ancient lost-wax casting techniques, showing the weeks of wax sculpting, multi-day ceramic shell building process, and extensive post-cast chasing work required to produce museum-quality bronze replicas. This brings the craftsmanship of the past to life.

This painstaking, often months-long effort to recreate a single object mirrors the archaeological endeavor of reconstructing a past world from fragments. It’s a reminder that behind every artifact is a complex chain of knowledge, labor, and time. This deep, process-oriented work, whether in a foundry or on a dig site, is the foundation of our heritage economy. The value it generates is significant, as analysis shows that archaeological development management contributes £218 million annually to the UK economy.

By understanding the effort required to create an object, we gain a deeper respect for the fragments we unearth and the stories they represent.

Key Takeaways

- Urban archaeology is not a simple layering system but the interpretation of a complex, disturbed ‘urban palimpsest’.

- The story is in the ‘interface layer’, where different historical periods collide, adapt, and build upon one another.

- Modern archaeology involves forensic analysis of hazards and a constant race against time during ‘rescue digs’ to preserve data before construction.

How Mass Tourism Erodes the Physical Fabric of Heritage Sites?

After a site is excavated, preserved, and opened to the public, a new chapter of interaction begins—one that brings its own form of erosion. While tourism is vital for funding and public engagement, it exerts immense physical pressure on fragile historic sites. The collective weight of millions of footsteps compacts soil, wears down ancient stone floors, and alters the microclimate of enclosed spaces. The moisture from breath can damage delicate frescoes, and the oils from hands can degrade ancient masonry. It’s a slow, insidious process, the 21st-century equivalent of wind and water erosion.

This threat is not just theoretical; it’s a pressing crisis. At coastal sites, the erosion is literal and dramatic. The Iron Age settlement at Knowe of Swandro in Orkney, for instance, is a stark example of a site being actively washed away by rising sea levels and storm surges—a rescue project battling against time itself. This is a direct parallel to the more gradual, human-caused erosion at popular inland sites. The scale of the threat is growing, with Historic England’s Heritage at Risk Register adding 155 new entries in the past year alone due to various factors, including neglect and environmental threats exacerbated by climate change.

Case Study: The Race Against Time at Knowe of Swandro

The Iron Age settlement at Knowe of Swandro in Orkney demonstrates the urgent race facing coastal archaeological sites. The University of Bradford-led excavation, named Rescue Project of the Year 2024, uncovered jewelry, bone tools, and a rare Iron Age glass toggle bead before rising sea levels claim the site permanently, highlighting the acute threat of physical erosion.

Managing this requires a delicate balance: providing access without sacrificing the very thing people have come to see. Solutions include raised walkways, visitor limits, “quiet days,” and using high-quality replicas for interactive displays. The challenge is to make visitors allies in preservation, helping them understand that their presence is part of the site’s ongoing story and that treading lightly is a form of respect for all the layers that came before.

The next time you walk through a historic city or ancient ruin, look down and consider the centuries of dialogue beneath your feet. Understanding this layered heritage is the first and most critical step towards ensuring it survives for future generations to read.

Frequently Asked Questions on Industrial Archaeology Hazards

What technology helps identify moisture-trapped rotting floors?

Drone-mounted thermal cameras can detect temperature variations indicating moisture accumulation and structural decay patterns from above, providing a safe initial assessment before any physical entry is attempted.

How can archaeologists detect heavy metal contamination without destructive sampling?

Portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) devices allow for the non-invasive identification of lead paint, mercury, and other heavy metal contamination on surfaces. This allows for rapid mapping of hazardous areas on a site.

What are industry-specific hazards beyond asbestos in old mills?

Anthrax spores in wool mill floors, mercury contamination near historic hat-making facilities, and a wide range of chemical residues from specific industrial processes (like tanning or dyeing) pose unique, site-specific risks that require historical research to anticipate.