Contrary to the popular image of simply patching up old walls, modern heritage conservation is a forensic science. The true work isn’t in the repair itself, but in the rigorous diagnosis of a structure’s “illnesses”—from chemical decay to environmental stress. Stabilizing historic masonry relies on a deep understanding of material pathology and an ethical commitment to interventions that are both minimal and, crucially, reversible.

The sight of a crumbling stone wall or a weathered monument evokes a powerful sense of history’s passage. For many, the instinct is to “fix” it—to patch the cracks, replace the stones, and make it whole again. This approach, however, often misses the fundamental ethos of modern conservation. A historic structure is not just an object to be repaired; it is a patient to be understood. Before a single tool is lifted, the heritage scientist’s first job is to perform a diagnosis, investigating the complex interplay of chemistry, environment, and original construction that causes the decay.

This process is far more than a simple visual inspection. It involves a deep dive into what we might call material pathology—identifying the specific “diseases” affecting the stone, wood, or metal. Is the damage from moisture ingress, chemical pollutants, biological growth, or the very stress of its own weight? Common solutions often focus only on the visible symptoms, but true conservation treats the underlying cause. The central challenge is not to make something look new, but to arrest its decay while preserving the authentic story etched into its very fabric.

This guide moves beyond the surface-level fixes to explore the core of a conservator’s work. We will delve into the scientific principles that dictate how and why materials fail, the critical ethical debates that shape every decision, and the advanced diagnostic tools that allow us to see what the naked eye cannot. The goal is not just stabilization, but preservation with integrity, guided by a single, paramount principle: that any action we take today must be undoable by the conservators of tomorrow.

This article explores the critical decisions and scientific challenges at the heart of heritage preservation. The following sections break down the key issues conservators face, from environmental threats to the ethical frameworks that guide their work.

Summary: The Science and Ethics of Stabilizing Historic Structures

- Why Humidity Fluctuations Destroy Victorian Woodwork Within Months?

- Reconstruction or Stabilization: Which Approach Saves Integrity?

- 3D Scanning vs Traditional Casting: Which is Safer for Roman Artifacts?

- The Grant Application Error That Costs Heritage Trusts Thousands

- How to Become a Certified Conservator Without a Chemistry Degree?

- The Rescue Dig: What Happens When a Skyscraper Foundation Hits a Roman Wall?

- Bronze Disease: How to Spot the Pale Green Powder That Eats Metal?

- Why Reversibility is the Golden Rule of Modern Conservation?

Why Humidity Fluctuations Destroy Victorian Woodwork Within Months?

Victorian buildings are famous for their intricate woodwork, but this feature is also their Achilles’ heel. Wood is a hygroscopic material, meaning it naturally absorbs and releases moisture from the air to stay in equilibrium with its surroundings. When humidity levels swing dramatically—from a damp, rainy week to a dry, centrally heated one—the wood is forced to expand and contract repeatedly. This constant movement generates immense internal stress within the material’s cellular structure, leading to warping, splitting, and the eventual failure of joints and finishes.

The damage is accelerated by a phenomenon known as the mechanosorptive effect, where the combination of moisture cycles and mechanical loads (like the wood’s own weight in a beam or arch) dramatically increases creep and deformation over time. This isn’t just theoretical; it’s a primary cause of structural failure in heritage buildings. Often, the root cause is not the wood itself, but issues baked in from the start. Research from the Victorian Building Authority highlights that poor design documentation and non-compliant construction are two of the most significant factors leading to moisture damage. A leaking roof or improperly sealed window, insignificant at first, can create a microclimate that subjects historic woodwork to a relentless cycle of expansion and contraction, ensuring its destruction within a few seasons.

Therefore, a conservator’s first line of defense is not repair, but environmental control. By monitoring and stabilizing humidity levels, they treat the “disease” of environmental fluctuation rather than just the “symptom” of a cracked panel. This preventative approach is fundamental to long-term preservation.

Reconstruction or Stabilization: Which Approach Saves Integrity?

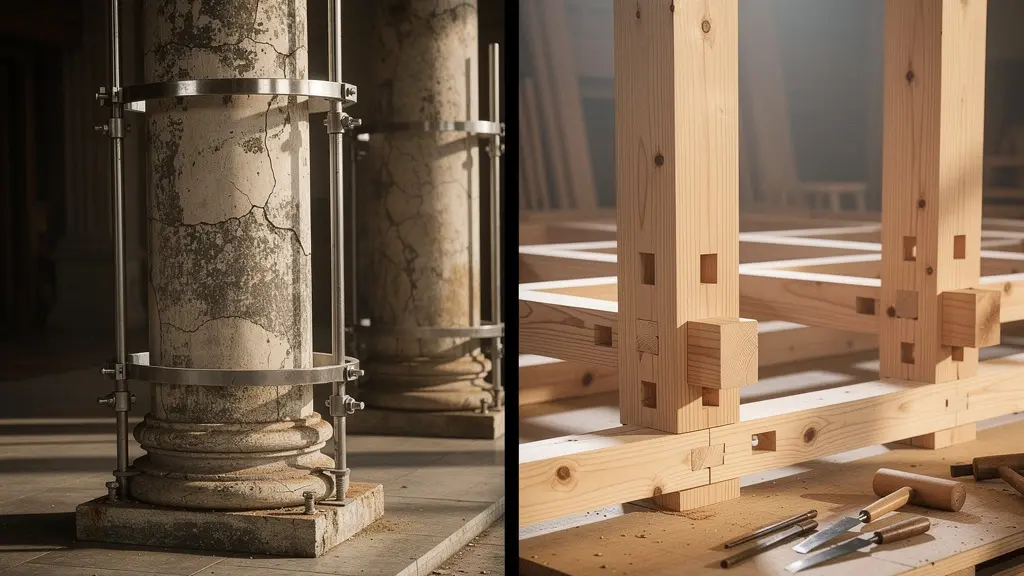

When faced with a deteriorating structure, conservators stand at a critical ethical crossroads: should they stabilize what remains, or reconstruct what has been lost? This is not a technical question but a philosophical one, with two major schools of thought. The first, often associated with Western conservation practice like the work on the Parthenon in Athens, prioritizes the authenticity of the original material. Here, the goal is stabilization. Modern materials like steel braces or resin consolidants may be used to support the ancient fabric, but the primary focus is on preserving the very stones that have survived through history. The scars of time are considered part of the object’s story.

The opposing philosophy is exemplified by cultural traditions such as the periodic rebuilding of the Ise Grand Shrine in Japan. Here, integrity is found not in the original materials, but in the authenticity of the craft and ritual. The shrine is completely dismantled and rebuilt with new wood every 20 years, using identical, centuries-old techniques. This ensures the preservation of intangible heritage—the skills, knowledge, and spiritual intent—rather than the physical components. Each approach saves a different kind of integrity.

The image below starkly contrasts these two philosophies: the painstaking work of supporting ancient, weathered stone versus the precise craft of renewing a structure with fresh materials.

As you can see, the choice between these paths is profound. Stabilization honors the object’s journey through time, while reconstruction honors the timeless human skill that created it. For most heritage projects, where a structure is considered historic once buildings are considered historic when they reach 50 years of age or greater, a hybrid approach is often taken, but the decision is always guided by a deep analysis of the site’s unique cultural and historical significance.

Ultimately, there is no single right answer. The conservator’s role is to facilitate an informed decision that best serves the specific heritage values of the site for future generations.

3D Scanning vs Traditional Casting: Which is Safer for Roman Artifacts?

Documenting an artifact is as important as preserving it. For centuries, the standard for creating a replica or detailed record was to make a physical mold, often using silicone or plaster. While effective for capturing shape, this method carries significant risks. The direct contact can lift fragile surface details, chemical reactions can stain the original material, and complex shapes with undercuts risk being broken during the mold’s removal. For irreplaceable objects like weathered Roman artifacts, this level of risk is often unacceptable.

This is where non-contact digital methods have revolutionized the field. 3D laser scanning and photogrammetry can capture an artifact’s geometry with sub-millimeter accuracy without ever touching it. More importantly, these technologies capture far more than just shape. They record color, texture, and even microscopic tool marks, creating a comprehensive “digital twin” of the object. This data can be used for virtual restoration, academic study, and monitoring for future decay, all without putting the original artifact at risk. The following table, based on best practices for stone restoration, clarifies the distinction, with information derived from expert sources like the International Masonry Institute’s guidance on stone restoration.

| Method | Contact Required | Risk of Damage | Data Captured | Future Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Laser Scanning | No physical contact | Zero risk to surface | Shape, color, texture, tool marks | Digital twin for monitoring, virtual restoration, 3D printing |

| Traditional Silicone Casting | Direct surface contact | Risk of undercuts breaking, chemical reactions, micro-abrasion | Shape only | Physical replica production only |

The adoption of digital documentation is not just about safety; it’s about expanding the possibilities of conservation and accessibility. To ensure this is done correctly, conservators follow a strict protocol.

Action Plan: Safe 3D Documentation Protocol for Heritage Artifacts

- Assess artifact condition and identify fragile areas before any documentation.

- Select non-contact scanning method based on material sensitivity (e.g., structured light for polished surfaces, laser for large-scale stonework).

- Create a baseline digital twin capturing both colorimetric (color) and surface texture data for future comparison.

- Use the scan data for virtual restoration testing, allowing conservators to try out repairs in a digital space before any physical intervention.

- Generate accessibility replicas via 3D printing, providing tactile experiences for visually impaired visitors without endangering the original object.

While traditional casting still has its place, for the most fragile and valuable pieces of our shared history, the move to a zero-contact digital workflow is an essential step in responsible stewardship.

The Grant Application Error That Costs Heritage Trusts Thousands

Securing funding is one of the most significant hurdles in heritage conservation. A well-written grant application can be the difference between a building saved and a building lost. Yet, a common and catastrophic error lies not in the project’s description, but in its budget: the failure to include a sufficient contingency fund. Historic structures are notorious for revealing unexpected problems once work begins. A project to repoint a wall might uncover severe structural decay behind the facade, or cleaning a fresco could reveal extensive water damage that was previously hidden.

These “known unknowns” are an inherent part of conservation work. Granting bodies are well aware of this, which is why conservation grant applications must include properly justified contingency budgets of 15-20% of the total project cost. An application that omits or significantly underestimates this fund is often viewed as naive and poorly planned, making it highly likely to be rejected. The applicant is essentially telling the funders they haven’t fully grasped the unpredictable nature of working with historic materials.

The consequences of this oversight are severe. A project that runs out of money midway through is a disaster. It can leave a structure more vulnerable than when it started, with exposed elements and incomplete repairs. As seen in numerous cases, water damage routinely tops the list of defects in buildings, and failing to budget for its unexpected discovery can turn a restoration project into a source of new and more expensive problems. A proper contingency fund is not “extra” money; it is an essential risk management tool that demonstrates professional foresight and a realistic understanding of the challenges ahead.

Therefore, building a robust contingency line item into every grant application is arguably the single most important financial step a heritage trust can take to ensure a project’s successful completion.

How to Become a Certified Conservator Without a Chemistry Degree?

The image of a conservator often involves a white lab coat and a deep knowledge of organic chemistry. While a scientific background is invaluable, it is not the only pathway into this vital field. The world of heritage preservation is vast and requires a diverse range of skills, many of which are rooted in traditional crafts and modern technology rather than academic science. As the International Masonry Institute notes, a combination of skills is essential to success.

Traditional craft skills and contemporary repair techniques are critical to the preservation of historic buildings and structures.

– International Masonry Institute, IMI Stone Restoration Training Programs

Many successful professionals enter the field through hands-on apprenticeships or by leveraging degrees in adjacent fields. An archaeologist, for example, already possesses a deep understanding of material culture and site analysis. An art historian can provide crucial context on an object’s significance. The key is to build upon an existing foundation with specialized, practical training. There are several viable routes:

- Heritage Craftsperson Route: Complete apprenticeships in stonemasonry, decorative plastering, or woodcarving through vocational training programs to master the physical techniques of repair.

- Conservation Technician Path: Specialize in a supporting role, such as operating environmental monitoring equipment, managing collections care, or performing preventative maintenance, which often does not require advanced chemistry.

- Digital Conservation Specialist: Focus on the technological side, becoming an expert in 3D scanning, photogrammetry, and GIS mapping for heritage sites—a rapidly growing and in-demand specialty.

- Adjacent Degree Leverage: Build on a degree in Archaeology, Art History, or Materials Science with targeted post-graduate certificates in conservation principles or techniques.

Furthermore, targeted certification programs can provide a direct entry point for those already in the trades. For instance, the International Masonry Institute offers specialized training, such as a 6-day Historic Masonry Preservation Certificate, designed specifically for journey-level craftworkers looking to transition into the restoration sector.

Ultimately, a passion for history, a meticulous nature, and a willingness to learn are just as important as a formal science degree in the multifaceted world of heritage conservation.

The Rescue Dig: What Happens When a Skyscraper Foundation Hits a Roman Wall?

It’s the scenario that is both a developer’s nightmare and an archaeologist’s dream: excavation for a new skyscraper uncovers a previously unknown Roman wall. In many cities with deep histories, such as London or Rome, this is a very real possibility. When it happens, a race against time begins, governed by strict preservation laws. The moment a significant find is made, all construction work must halt, and a process known as “preservation by record” or, in more urgent cases, a “rescue dig” is initiated.

The first priority is not removal, but documentation. Archaeologists and digital conservation specialists swarm the site, using 3D scanners and high-resolution photography to create a perfect digital replica of the find in its original context (in situ). Every stone, mortar joint, and associated artifact is meticulously recorded. This record is, in itself, a form of preservation. Once the documentation is complete, a critical decision must be made, usually in negotiation between the developers, city planners, and heritage authorities. Can the new building be redesigned to incorporate the wall? Or must the wall be moved?

If relocation is the only option, an incredibly delicate and complex engineering operation begins. This is not a simple demolition. Conservators may use diamond wire saws to cut the structure into manageable blocks, as depicted in the detailed image below, ensuring clean cuts that can be seamlessly reassembled later.

Each block is labeled, its position recorded, and then carefully lifted and transported to a new location for reconstruction, often in a museum or public display. This entire process is triggered because the structure meets the criteria of being historic, a threshold often legally defined by age. This process of rescue archaeology represents conservation at its most dynamic and high-stakes, balancing the pressures of modern development with the duty to protect our past.

It is a powerful reminder that history is not just in museums; it is often lying just inches beneath our feet, waiting for a chance to be saved.

Bronze Disease: How to Spot the Pale Green Powder That Eats Metal?

Not all green on an ancient bronze artifact is a good thing. A stable, dark green or bluish patina is a protective layer of copper carbonates that forms over centuries and is a desirable sign of age and authenticity. However, a fuzzy, pale green, powdery substance is a sign of a malignant corrosion known as bronze disease. This is not a biological infection but a destructive chemical reaction. When bronze artifacts containing chloride salts (often from being buried in the ground) are exposed to moisture and air, a runaway cyclical reaction begins that can completely destroy the object, leaving behind nothing but a pile of green powder.

Identifying it early is critical. The key distinction is its physical nature. A stable patina is hard and integral to the metal surface. Bronze disease, however, is friable and can be easily flaked off with a fingernail or a wooden tool. Once identified, treatment must begin immediately to arrest the corrosion. The process is a form of chemical “detox” for the artifact and must be done in a controlled lab environment.

- Mechanical Cleaning: The first step is to physically remove all visible powder under a microscope using tools like a scalpel or a soft brush to prevent it from seeding new corrosion.

- Chloride Extraction: The artifact is then submerged in a chemical bath, typically a solution of sodium sesquicarbonate, which slowly leaches the chloride ions out of the metal’s porous structure. This process can take weeks or even months.

- Sealing and Storage: Once the chloride levels are negligible, the object is carefully dried and sealed with a microcrystalline wax or lacquer to create a barrier against future moisture exposure. It must then be stored in a low-humidity environment to prevent any recurrence.

As with all conservation, the guiding principle is to use the gentlest methods possible to achieve the desired level of clean without harming the surface. Harsher treatments can create more porosity in the metal, ironically making it more susceptible to future damage. Treating bronze disease is a perfect microcosm of the conservator’s craft: a delicate balance of chemical knowledge, patient intervention, and a deep respect for the object’s survival.

Spotting that pale green powder and knowing it is a cry for help, not a mark of age, is a crucial skill for anyone entrusted with the care of our metallic heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Conservation as Diagnosis: The most critical work is understanding an object’s material “illnesses” before any treatment is considered.

- An Ethical Choice: Every project involves a core decision between stabilizing original material (authenticity of substance) and reconstructing it (authenticity of craft).

- The Reversibility Doctrine: Modern conservation is guided by the ethical mandate that any intervention made today should be removable by future generations with more advanced knowledge.

Why Reversibility is the Golden Rule of Modern Conservation?

In the past, restoration often meant permanent, irreversible changes. Old mortars were replaced with hard Portland cement that damaged the surrounding stone, and fragile surfaces were coated with synthetic resins that yellowed and became impossible to remove. Modern conservation is defined by its rejection of this approach. The single most important principle guiding a conservator’s work today is reversibility. This golden rule dictates that any material added to an original object—be it an adhesive, a consolidant, or a structural support—should be removable in the future without damaging the artifact.

This principle is an act of profound intellectual humility. It acknowledges that our knowledge and technology are imperfect and will inevitably be surpassed. A treatment that seems state-of-the-art today may be revealed as damaging in fifty years. By ensuring our work is reversible, we give future generations the option to re-treat the object with their more advanced methods. It preserves not just the object, but also its potential for better care in the future. As the International Masonry Institute states, thoughtfully and appropriately designed restoration projects can preserve the integrity of the masonry building and continue its life for future decades. The goal is to be a temporary custodian, not a final author.

This applies to everything from the glues used to repair ceramics to the large-scale supports for buildings. For example, when stabilizing a structure like the Monadnock Building in Chicago, a 16-story building with 6-foot thick base walls, any new materials introduced would be carefully chosen for their chemical stability and removability. Reversibility is the ultimate safeguard, ensuring that our attempts to save history do not inadvertently cause its final demise.

The next time you visit a historic site and see the subtle signs of repair, look closer. The best conservation work is often the least visible, a quiet, respectful intervention that ensures the structure’s story can be told for centuries to come, guided by the wisdom to know that our role is to preserve, not to permanently alter.