The desire to share the beauty of medieval manuscripts clashes with the reality that light and air are their mortal enemies. The solution isn’t to hide them away forever, but to shift our thinking from simple rules to active management. True preservation involves treating each book as a delicate chemical ecosystem, implementing a strict “light budget” to control cumulative exposure, mastering material-specific environmental controls, and understanding the chemistry of decay before it becomes irreversible.

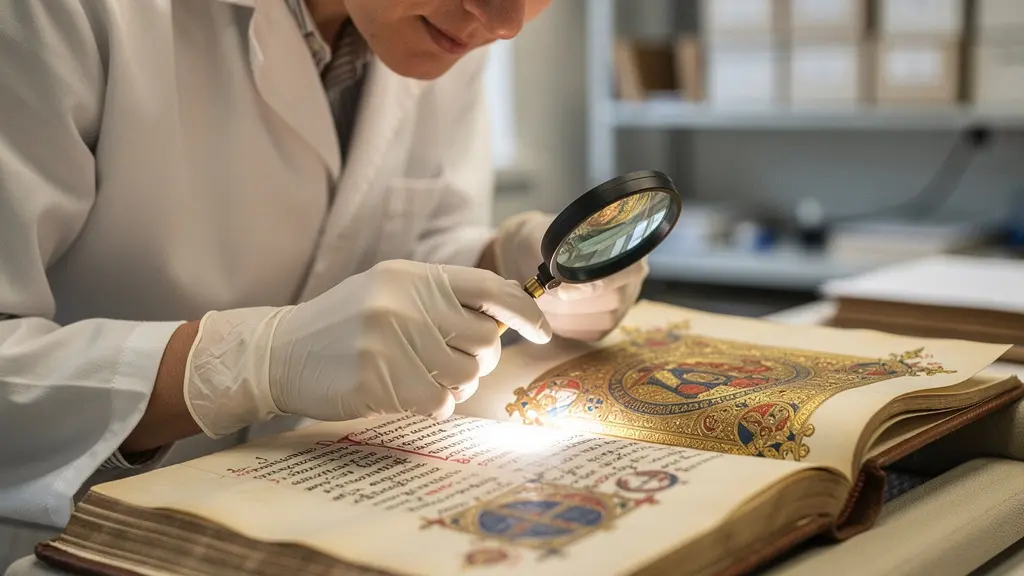

There is a certain magic in a medieval manuscript. It’s in the hushed scent of old parchment and leather, the weight of history in your hands, and the incredible detail of an illuminator’s brushstroke. For curators and librarians, the deep desire to share this magic with the world is constantly at odds with our primary duty: to preserve it. We are the ethical custodians of these fragile objects, and the very act of display exposes them to their greatest enemies: light, humidity, and the unstable chemistry of their own creation.

The common advice—use low light, control the climate, digitize everything—is a starting point, but it barely scratches the surface. This advice treats the manuscript as a static object when it is, in fact, in a constant state of slow, chemical reaction. True conservation is not a passive checklist; it is an active, scientific, and deeply philosophical practice. It demands that we understand the very materiality of the object, from the collagen fibers of animal skin to the corrosive potential of iron gall ink.

What if the key to preservation wasn’t just following rules, but understanding the living chemistry of the book itself? This is the perspective of the modern conservator. It is a shift from simple prevention to holistic environmental management, treating exposure not as a single event, but as a cumulative dose that must be carefully budgeted over the object’s lifetime.

This guide explores that professional mindset. We will delve into the science of light damage, the unique behaviors of vellum and paper, the paradoxes of digitization, the insidious nature of ink corrosion, and the foundational principle that governs all modern conservation work. By understanding the ‘why’ behind the ‘how’, we can make more informed decisions to protect these irreplaceable treasures for centuries to come.

Summary: A Conservator’s Guide to Manuscript Display

- Lux Hours: How Long Can a Page Be Exposed Before Permanent Damage Occurs?

- Animal Skin vs Wood Pulp: Why Vellum Reacts Differently to Humidity?

- Touching the Screen, Not the Book: Does Digitization Save the Original?

- Iron Gall Ink Burn: What to Do When the Words Are Eating the Paper?

- Cold Storage: Is Freezing the Only Way to Save Modern Wood Pulp Paper?

- Smartphone Flash in Dark Rooms: The Damage You Don’t See

- Solvent-Free Oil Painting: Is It Really Possible to Ditch Turpentine?

- Why Reversibility is the Golden Rule of Modern Conservation?

Lux Hours: How Long Can a Page Be Exposed Before Permanent Damage Occurs?

The most common misconception about light damage is that it’s caused by brightness. In reality, the true enemy is cumulative exposure. Every photon that strikes a pigment is like a tiny hammer blow, and enough of them will eventually cause irreversible fading. This is why conservators think in terms of a “light budget”—a finite amount of exposure an object can receive over a period. It’s a fundamental shift from “is the light low enough?” to “how much of the object’s ‘light life’ are we spending today?”

This approach allows for quantifiable and sustainable exhibition planning. According to internationally accepted conservation standards, the maximum safe annual exposure for highly sensitive materials like manuscripts is just 12,500 lux hours. This means a page displayed at 50 lux (a common museum level) uses up its entire yearly budget in just 250 hours, or about a month of exhibition time. This damage is permanent and cumulative; the light budget, once spent, is gone forever.

To visualize this gradual destruction, conservators use tools like Blue Wool standard test strips. These calibrated textile samples fade at a predictable rate, providing a tangible measurement of the light energy in a space. Seeing the gradient of fading on a test strip makes the abstract concept of cumulative damage chillingly real. It’s a constant reminder that for every hour a manuscript is on display, a tiny, unrecoverable piece of its vibrancy is lost.

Action Plan: Implementing a Light Budget System

- Classify Materials: Identify and categorize manuscript pigments by their known light sensitivity, such as the highly fugitive nature of some organic dyes versus the relative stability of carbon ink.

- Measure Levels: Use a calibrated lux meter to take precise readings at the object’s exact position within the display case, accounting for any focused spotlights.

- Calculate Exposure: Use the formula (Lux × Hours of Display) to calculate the cumulative lux-hour exposure for each exhibition day and track it against the annual budget.

- Document Everything: Maintain a meticulous log for each object in a collection management system, recording every period of display and its calculated light dose.

- Automate Rotation: Establish a protocol to automatically rotate the manuscript or turn the page once it reaches 80% of its annual light budget, ensuring a buffer for unexpected exposure.

Animal Skin vs Wood Pulp: Why Vellum Reacts Differently to Humidity?

A manuscript is not a uniform object; its reaction to the environment is dictated by its very substance. The two primary substrates, vellum (animal skin) and paper (wood pulp), engage in a completely different chemical ballet with atmospheric moisture. Vellum is composed of collagen protein fibers, the same material as our own skin. It is intensely hygroscopic, meaning it readily absorbs and releases moisture, and it possesses a powerful “memory.” If it has been folded for centuries, it will desperately try to return to that state when exposed to humidity, causing cockling and stress on the inks.

Paper, made of cellulose plant fibers, is also hygroscopic but behaves more predictably. It tends to swell and contract more uniformly. However, older, acidic paper is far more susceptible to chemical degradation like foxing (brown spots) when humidity rises. This distinction is critical for environmental control. A single set of RH (Relative Humidity) and temperature settings is a compromise that serves neither material perfectly. As the Library of Congress’s treatment of medieval fragments shows, working with parchment requires incredible precision. Their conservators used a Gellan gum gel with a water-ethanol mixture to locally humidify and flatten creases, a testament to the surgical approach needed for collagen-based materials.

The following table, based on established conservation science, breaks down these fundamental differences.

| Property | Vellum/Parchment | Wood Pulp Paper |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Collagen protein fibers | Cellulose plant fibers |

| Humidity Response | Hygroscopic with ‘memory’ effect | |

| RH Fluctuation Impact | Cockling, dimensional changes | Weakening, foxing potential |

| Optimal RH Range | 45-55% | 35-50% |

| pH Environment | Naturally alkaline | Often acidic (pre-1950) |

Touching the Screen, Not the Book: Does Digitization Save the Original?

In the digital age, creating high-resolution surrogates is often presented as the ultimate preservation solution. The logic is simple: if people can access a perfect digital copy online, the original can rest safely in a dark vault. This, however, is a dangerous oversimplification and a prime example of the preservation paradox. The very act of creating the digital version can be one of the most stressful events in a manuscript’s life.

Each page must be positioned, handled, and exposed to the intense, focused light of a scanner. For tightly bound volumes, forcing them flat on a scanner bed can place immense strain on the spine and sewing structure, causing damage that a thousand readers might not. As conservation specialists noted during a symposium on this topic:

Digitization itself can inflict damage through light exposure, handling stress, and binding strain – it’s a preservation paradox where the act of creating access potentially accelerates deterioration.

– Conservation specialists, From Parchment to Pixel symposium

Furthermore, the assumption that digital access reduces demand for the original is often false. Research has uncovered a “rebound effect,” where widely accessible digital versions can paradoxically increase public and scholarly interest, leading to more requests to see the authentic object. Digitization is an indispensable tool for access and scholarship, but it is not a substitute for the physical conservation of the original artifact. It is one part of a holistic strategy, not the final chapter.

Iron Gall Ink Burn: What to Do When the Words Are Eating the Paper?

Of all the inherent vices in a manuscript, iron gall ink is perhaps the most poetic and destructive. For centuries, it was the standard ink of the Western world, made from iron salts, tannins from oak galls, and a binder. Its fatal flaw is its chemistry. An excess of iron ions in the formula creates a highly acidic environment that, over time, catalyzes the oxidation of the cellulose in the paper. This process, known as ink corrosion or “burn,” literally causes the words to eat through the page, leaving behind a brittle, lace-like remnant.

This degradation is accelerated by high humidity, which fuels the chemical reaction. Halting this process is one of the greatest challenges in paper conservation. Intervention is complex and carries significant risks. One of the most advanced methods is the British Library’s protocol, which involves a two-step aqueous treatment. A calcium phytate solution is used to chelate, or bind, the destructive free iron ions, effectively arresting the corrosive reaction. This is followed by a calcium bicarbonate bath to deacidify the paper and create an alkaline buffer against future acid attack.

However, as conservators who developed the protocol emphasize, this treatment is not for every manuscript. Many objects are simply too fragile to withstand being immersed in water. In these heart-breaking cases, the only ethical option is non-intervention. The conservator’s role shifts to palliative care: creating a strictly controlled microclimate (low temperature and stable RH between 45-55%) to slow the inevitable decay as much as possible, and documenting its state for the future. It is a humbling admission that sometimes, the best we can do is manage a graceful decline.

Cold Storage: Is Freezing the Only Way to Save Modern Wood Pulp Paper?

While we often associate preservation with ancient vellum, some of the most vulnerable materials in our collections are relatively modern. Paper produced between roughly 1850 and 1990 was often made from acidic wood pulp, a legacy of industrial manufacturing processes. This paper contains the seeds of its own destruction. The acid within the cellulose fibers relentlessly breaks them down, causing the paper to become yellow, brittle, and eventually crumble to dust, even in a perfectly dark room.

For these materials, standard “cool and stable” storage is not enough; the chemical decay continues at an alarming rate at room temperature. The only proven method to drastically slow this process is cold or frozen storage. By lowering the temperature to near or below freezing, we can reduce the rate of these destructive chemical reactions by a factor of hundreds. This is why major institutions maintain specialized cold storage vaults for their most endangered modern collections, including acidic books and color photographs, whose dyes are notoriously unstable.

Crucially, this approach is entirely unsuitable for most medieval manuscripts. The collagen structure of vellum contains water, and freezing it could cause ice crystals to form, physically rupturing the fibers and causing catastrophic, irreversible damage. This highlights a core principle of conservation: there is no universal solution. Each material requires a specific prescription based on its chemical composition and inherent vices.

| Material | Optimal Temperature | Storage Method | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medieval Vellum | 16-20°C | Cool, stable | Physical damage from freezing |

| Iron Gall Manuscripts | 14-18°C | Cool with RH control | Accelerated oxidation if warm |

| Acidic Wood Pulp (1850-1990) | -20°C to 2°C | Freezing/cold storage | Rapid deterioration at room temp |

| Color Photographs | -3°C to 2°C | Cold storage | Dye fading and color shift |

Smartphone Flash in Dark Rooms: The Damage You Don’t See

In a dimly lit gallery, the sudden, brilliant burst of a smartphone flash can feel like a violation. For a manuscript, it is a physical assault. The damage from flash photography is not just about the visible brightness; it’s about the incredible intensity and the unseen spectrum of the light. Research from the Getty Conservation Institute reveals that a single xenon camera flash can deliver a light dose equivalent to displaying an object at 50 lux for an entire hour. In an instant, a significant portion of the object’s annual light budget is consumed.

Beyond the intensity, these flashes emit a spike of high-energy ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which is particularly destructive to organic materials like paper, pigments, and binders. It acts as a powerful catalyst for the chemical reactions that cause fading and embrittlement. This is why “No Flash Photography” signs are not merely suggestions; they are a critical line of defense for irreplaceable artifacts.

Museums and libraries deploy sophisticated environmental design to combat this threat. It’s a subtle form of defensive architecture. Display cases are often made with museum-grade anti-reflective or laminated glass that filters out over 99% of UV radiation. Some cases use polarizing filters or are angled specifically to cause glare that ruins a flash photograph. Other strategies include positioning objects deep within a case, beyond the effective range of a typical flash, or using motion-sensor lighting that dims when no one is near, reducing the overall cumulative exposure. These are the invisible systems working tirelessly to protect history from a moment of photographic impulse.

Solvent-Free Oil Painting: Is It Really Possible to Ditch Turpentine?

In the world of painting, there’s a growing movement toward solvent-free practices, ditching toxic materials like turpentine for safer, modern alternatives. This same concept has a powerful, if metaphorical, parallel in the world of manuscript conservation. Our “solvents” are not in a jar, but are silently off-gassing from the very materials we use to protect the objects.

A poorly constructed display case can become a toxic micro-environment. Materials like wood, certain adhesives, fabrics, and paints can release Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), including acids like acetic and formic acid. Over time, these airborne pollutants settle on the manuscript, accelerating the breakdown of cellulose and contributing to the same kind of acidic decay seen in iron gall ink. As museum conservation specialists aptly put it:

The off-gassing from poorly-made display cases acts like the ‘turpentine’ of conservation – VOCs from wood, adhesives, and paints slowly damage manuscripts just as solvents affect paintings.

– Museum conservation specialists, International Institute for Conservation guidelines

The solution is to create a “solvent-free” micro-environment inside the case. This is achieved through meticulous material selection (using inert metals, glass, and archival-quality boards) and active pollution control. Many modern display cases, like those used at the Fitzwilliam Museum, incorporate scavengers like activated carbon cloth or molecular sieves (zeolites). These materials act like sponges, trapping harmful VOCs from both the off-gassing of construction materials and any pollutants infiltrating from the outside air. It is a commitment to creating a pristine, stable atmosphere where the manuscript can rest, safe from the invisible chemical assault of its own enclosure.

Key Takeaways

- Light damage is cumulative and irreversible; preservation requires managing a strict, quantifiable lux-hour “budget” for each object.

- Material dictates the method: Vellum (collagen) and paper (cellulose) have fundamentally different reactions to humidity and require distinct environmental controls.

- All interventions carry risk. Actions like digitization or chemical treatment must be carefully weighed against the core principle of reversibility, as some damage cannot be undone.

Why Reversibility is the Golden Rule of Modern Conservation?

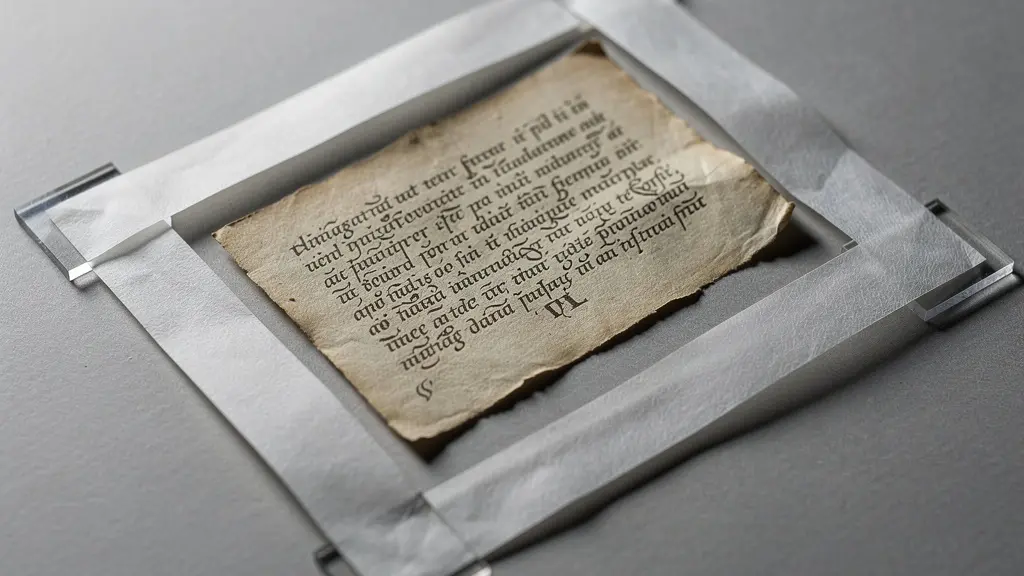

If there is one principle that underpins all of modern conservation ethics, it is reversibility. This golden rule dictates that any treatment or repair applied to an artifact should, in theory, be undoable by a future conservator. This is not because we expect to make mistakes, but because we have the humility to know that future generations will have better science, better techniques, and a different understanding of the object. Our role is not to permanently alter the object, but to stabilize it, leaving a path open for those who come after us.

This philosophy is a direct response to the destructive “restorations” of the past, where missing sections were repainted and pages were aggressively bleached, permanently changing the object’s historical integrity. Today, a repair to a torn page might be made with a delicate Japanese tissue paper and a stable, pH-neutral adhesive that can be safely removed with a specific solvent years later. This commitment is so profound that ICA guidelines for exhibition planning emphasize the need for meticulous documentation, creating a record of all materials and conditions to enable informed, reversible decisions for the next 100 years.

This image of a reversible mount perfectly illustrates the principle in practice. The manuscript is not glued down but gently held by inert corners and hinges, a method that is both secure for display and completely removable without a trace. However, as the Canadian Conservation Institute wisely notes, this principle has its limits. The damage caused by light fading and ink corrosion is the ultimate example of irreversibility. No future technology can un-fade a pigment or un-burn a page. This is why prevention through meticulous environmental control is not just the best option—it is the only truly ethical one.

Adopting this conservator’s mindset—one of scientific understanding, material respect, and ethical humility—is the most profound step we can take. It transforms our role from simple gatekeepers to active, thoughtful stewards, ensuring these windows into our past remain open for the future. Start today by implementing a light budget and documenting the unique conditions of every object in your care.