The magic of theatre relies on a fragile, collective state of ‘shared consciousness’ which can be neurologically ‘infected’ and collapsed by a single distraction.

- Audience distraction is not an individual problem but a contagious phenomenon that spreads inattentiveness, actively dismantling the group’s focused reality.

- Physical and psychological factors, from seating position to our one-sided bonds with characters, dictate our susceptibility to this collapse of belief.

Recommendation: To preserve the magic, an audience must understand they are not passive observers but active co-creators of the theatrical illusion, with a shared responsibility to protect its delicate ecosystem.

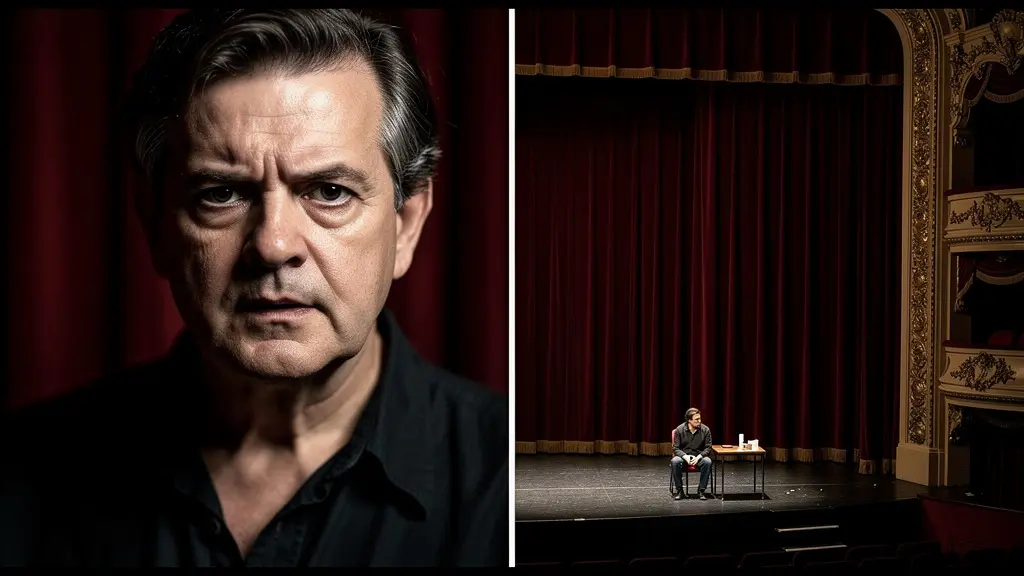

We have all felt it. That sacred moment in a darkened theatre when the world outside dissolves and the reality on stage becomes the only one that matters. This willing surrender, this pact between performer and spectator, is what we call the “suspension of disbelief.” It’s the invisible architecture that supports the entire theatrical experience. For generations, the discussion around preserving this state has revolved around simple etiquette: turn off your phones, don’t talk, respect the actors. These are valid points, but they only skim the surface, treating the audience as a collection of individuals who must behave.

This perspective misses the fundamental truth of live performance. The conventional wisdom blames failed immersion on a lack of personal focus or a subpar production. It assumes the pact is a series of individual, isolated contracts. But what if the suspension of disbelief is not a personal choice, but a fragile, collective state of ‘shared consciousness’? What if the audience is not 500 separate minds, but a single, temporarily-formed organism, breathing and focusing as one? From this viewpoint, a distraction is not a minor annoyance. It is a virus.

This article dissects the mechanics of that broken spell. We will move beyond etiquette to explore the psychology and neuroscience of theatrical immersion. We will investigate how a single glowing screen can trigger a cognitive contagion, how your physical seat rewires your emotional connection, and why the silence between words can hold more power than a scream. By understanding the forces that unravel this shared reality, we not only become better audience members but also gain a deeper appreciation for the profound, delicate magic we are invited to co-create.

To fully grasp the intricate dynamics at play, this analysis will explore the various elements that can either fortify or fracture the theatrical illusion. The following sections break down these critical components, from external disruptions to the internal psychology of the audience.

Summary: The Fragile Architecture of Theatrical Belief

- Glowing Screens: How One Phone Can Ruin the Immersion for 500 People?

- Stalls vs Circle: How Viewing Angle Changes Your Emotional Connection to the Play?

- The Post-Theatre Blues: Why Do You Feel Empty After a Great Performance?

- Reading Between the Lines: How to Spot What the Characters Are Not Saying?

- The Power of the Pause: Why Silence is Louder Than Screaming in Drama?

- Telling the Story Through Movement: How Blocking Directs the Audience’s Eye?

- Interactive Art: What Happens When the Audience Refuses to Play Along?

- How to Navigate the Cramped Comfort of Grade-Listed West End Theatres?

Glowing Screens: How One Phone Can Ruin the Immersion for 500 People?

The luminous rectangle of a phone in a dark theatre is more than a simple distraction; it’s a contagion. The failure of immersion isn’t just about the one person checking their messages. It’s about the signal of non-belief they transmit to everyone around them. Our brains are hardwired for social cues, and a glowing screen is a powerful one. It says, “This fiction is not real. The world outside is more important.” This single act shatters the collective effervescence, the shared emotional energy that binds an audience together. A 2023 study of French theatre audiences confirmed this phenomenon, finding that this shared energy is a crucial mediator of individual enjoyment. When the collective field is disrupted, personal immersion becomes exponentially harder to maintain.

This isn’t just a feeling; it’s a documented psychological process known as attention contagion. Our focus is not an isolated fortress; it’s porous and highly susceptible to the state of those around us. Research from 2024 demonstrates that participants seated near inattentive individuals report lower attentiveness and perform worse on subsequent tasks. In a theatre, one person’s wandering focus creates a ripple effect, unconsciously pulling neighbours out of the shared fiction. The light doesn’t just draw the eye; it breaks the spell by reminding hundreds of brains that the emperor on stage is just an actor and the palace is just a set. The theatrical contract is a group activity, and one person tearing up their copy can void it for the entire row.

Ultimately, a phone doesn’t just introduce a competing light source; it introduces a competing reality, and in doing so, it poisons the delicate, shared consciousness required for theatrical magic to exist.

Stalls vs Circle: How Viewing Angle Changes Your Emotional Connection to the Play?

Your physical position in a theatre is not a neutral variable; it is an active agent in shaping your emotional journey. The distance and angle from which you view the stage fundamentally alter your relationship with the performance, creating a spectrum of experiences from intimate connection to detached observation. Sitting in the front rows of the stalls, you are enveloped by the world of the play. You see the subtle flicker in an actor’s eyes, the bead of sweat on their brow, the minute tension in their hands. This proximity fosters an intense, personal connection, making you a confidant to the characters’ plights. You are inside the story.

Conversely, a seat in the upper circle or balcony offers a panoramic, god-like perspective. You see the full stage, the director’s grand design, the patterns of movement, and the architectural sweep of the blocking. This is the perspective of the strategist, the analyst. You are better positioned to appreciate the intellectual craft of the production, but the raw, visceral emotion is blunted by distance. The characters become figures in a landscape rather than living, breathing souls sharing your space. This physical distance creates emotional distance, transforming a potential gut-punch into an intellectual exercise.

This is compounded by the architectural realities of historic theatres, where many seats offer compromised views. For instance, The Theatres Trust estimated in 2003 that as many as 60% of seats in some older venues had partially obstructed sightlines. A pillar blocking a key entrance or a safety rail bisecting the stage is a constant, physical reminder that you are outside the illusion, an observer peering in, rather than a participant within it. The architecture itself can enforce a state of non-belief.

Therefore, choosing a seat is not merely a practical decision about sightlines; it’s a choice about what kind of emotional and psychological contract you wish to sign with the performance.

The Post-Theatre Blues: Why Do You Feel Empty After a Great Performance?

The feeling of emptiness that can follow a powerful performance is not a sign of a flawed experience, but of a deeply successful one. This “post-theatre blues” is the emotional echo of a broken bond, a phenomenon best understood through the lens of parasocial relationships. These are the one-sided, intimate connections we form with media figures, or, in this case, fictional characters. For two hours, you have invested emotionally in their lives, their struggles, and their triumphs. The actors and the environment have created a space where this connection feels real, reciprocal, and immediate. Your brain, for all its sophistication, processes this intense, focused empathy as a genuine social bond.

The curtain call is therefore not just an ending; it’s a breakup. The abrupt severance of this bond can trigger a form of grief. The characters you have come to know and care for are suddenly gone, the world they inhabited dismantled. The sense of loss is real because the emotional investment was real. The intensity of this feeling is a testament to the power of the performance to create a believable, inhabitable reality. The recent explosion in academic interest, where more studies on parasocial relationships were published between 2016 and 2020 than in the previous 60 years, highlights how central these one-sided bonds are to our experience of media and art.

This experience is amplified in theatre compared to film or television. The liveness, the shared space, and the knowledge that the performers are breathing the same air as you deepens the perceived intimacy and trust. The illusion of reciprocity is stronger. When the lights come up, the stark contrast between the intense emotional world you just left and the mundane reality of shuffling out of a theatre can be jarring. This “emotional hangover” is the price of admission for a journey that truly mattered.

It is a strange and beautiful paradox: the more completely a play makes you believe, the more acute the sense of loss when you are forced to stop.

Reading Between the Lines: How to Spot What the Characters Are Not Saying?

The true artistry of dramatic writing and performance often lies not in the words that are spoken, but in the vast, charged space of what is left unsaid. This is the realm of subtext, where characters’ true intentions, fears, and desires ripple beneath the surface of their dialogue. Learning to read this unspoken language is the key to unlocking a deeper, more rewarding theatrical experience. It requires a shift in focus from merely listening to the script to observing the entire theatrical event as a complex tapestry of signals. Subtext is revealed through contradiction: when a character’s body language screams “no” while their words whisper “yes,” or when they obsessively discuss the weather to avoid a painful truth sitting between them.

The process of decoding subtext is an active, investigative one. It involves listening for the action verb behind each line. Is the character pleading, attacking, deflecting, or seducing with their words? This underlying action is often more revealing than the literal meaning of the sentence. Furthermore, pay close attention to informational gaps. Great playwrights deliberately leave out details, forcing the audience to become detectives, to infer history and motivation from the clues provided. These gaps are not flaws; they are invitations to engage, to co-create the story’s meaning. The ability to recognize these patterns is a skill that transforms you from a passive spectator into an active participant in the drama.

Your Checklist: Detecting Character Subtext

- Focus on physical movements and gestures when characters are silent.

- Listen for the underlying action verb behind each spoken line.

- Identify informational gaps that require audience inference.

- Watch for contradictions between words and body language.

- Pay attention to what characters or topics they actively avoid discussing.

This engagement is precisely what forges the parasocial bond. A study testing the application of Parasocial Interaction (PSI) scales found they could be applied to theatre audiences without any changes, proving our psychological engagement with live characters follows the same patterns as with those on screen. By filling in the subtextual gaps, we invest a part of ourselves in the characters, making their reality more solid and our connection more profound.

Ultimately, the richest stories are told in the silences, and learning to listen to them is what separates a casual theatre-goer from a true connoisseur.

The Power of the Pause: Why Silence is Louder Than Screaming in Drama?

In a world saturated with noise, the most powerful tool in a dramatist’s arsenal is often silence. A well-placed pause on stage can create more tension, reveal more character, and provoke more thought than any line of dialogue. Its power lies in its ability to disrupt our expectations. We are conditioned to a certain rhythm of speech and interaction. A sudden, extended silence breaks this pattern, jolting the audience to attention. It creates a vacuum that we, as observers, desperately try to fill with meaning. What is happening in this gap? What is being decided, feared, or remembered? The silence becomes a canvas onto which we project the play’s unspoken tensions.

This is not just poetic interpretation; it’s rooted in neuroscience. As one piece of research frames it, a well-timed pause “violates the predicted rhythm of speech, triggering a ‘prediction error’ signal that floods the brain with attention.” The following is a powerful expression of this idea:

A well-timed pause violates the predicted rhythm of speech, triggering a ‘prediction error’ signal that floods the brain with attention.

– Neuroscience researchers, Based on attention and prediction research

In that moment of cognitive disruption, our brains are fully engaged, working overtime to understand why the expected sound did not arrive. It is in this state of heightened alertness that an actor can land an emotional blow with just a look, a gesture, or the eventual, long-awaited next word. The silence magnifies the importance of what precedes and follows it, acting as a frame for the most critical moments of the play.

Consider the difference between a character screaming “I hate you!” and a character who, asked if they are angry, simply meets their accuser’s gaze and says nothing. The scream is a release of tension; the silence is a compression of it. It is active, not passive—a weapon, a shield, or a confession, all without a single word. It forces the audience to lean in, to become collaborators in the creation of meaning, and in doing so, deepens their immersion in the world of the play.

It is in these moments of profound quiet that the theatre truly speaks, demonstrating that what is unsaid can often be the most deafening part of the performance.

Telling the Story Through Movement: How Blocking Directs the Audience’s Eye?

Blocking—the precise staging of actors on stage—is the unspoken grammar of theatrical storytelling. It is a visual language that communicates relationships, power dynamics, and emotional states far more effectively than dialogue alone. A director uses the stage as a canvas and the actors as focal points, composing a series of living pictures that guide the audience’s attention and shape their interpretation. Where a character stands in relation to others, how they move, and the physical space between them is a constant stream of subtextual information. This choreography is not arbitrary; it is a meticulously crafted tool for manipulating focus and conveying meaning.

The language of stage position is rooted in a psychological framework known as proxemics, which studies how human beings use space. Directors use this “proxemic grammar” to define character relationships without a single word. As the following table illustrates, the physical distance between characters directly translates into a perceived emotional distance for the audience, a concept that can be broken down into clear zones of interaction.

| Distance Zone | Physical Space | Theatrical Meaning | Audience Perception |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intimate | 0-1.5 feet | Love, conflict, secrets | High emotional intensity |

| Personal | 1.5-4 feet | Friendship, conversation | Character connection |

| Social | 4-12 feet | Formal interaction | Professional relationship |

| Public | 12+ feet | Performance, speeches | Authority, distance |

A character who consistently occupies upstage positions (further from the audience) may be perceived as distant or powerful, while one who frequently comes downstage feels more intimate and vulnerable. Two characters standing far apart at the start of a scene who slowly move closer together are visually narrating a story of growing intimacy or confrontation. The director’s job is to orchestrate these movements to control the audience’s visual field, making certain interactions the undeniable focal point while rendering others as background noise. This deliberate manipulation of focus ensures that the audience’s gaze lands exactly where the story’s emotional heart is beating fastest.

In this way, blocking becomes more than just movement; it is the physical manifestation of the play’s psychological and emotional architecture, telling a story that the ears might miss but the eyes understand perfectly.

Interactive Art: What Happens When the Audience Refuses to Play Along?

The rise of immersive and interactive theatre has challenged the traditional, passive role of the spectator, recasting them as a co-author of the experience. This form of theatre breaks the “fourth wall” and invites the audience directly into the narrative. However, this invitation comes with a significant risk: what happens when the audience refuses to accept? This refusal is rarely born of malice. More often, it stems from a deep-seated and entirely understandable human fear: stage fright. As research into immersive theatre psychology reveals, many people associate “audience participation” with the cringeworthy awkwardness of being put on the spot, a prospect that triggers genuine anxiety.

When an audience member “refuses to play along”—by not responding to an actor’s prompt, or by physically retreating from an interaction—they are not necessarily rejecting the fiction. They are often protecting themselves from perceived social peril. The suspension of disbelief in this context requires a level of vulnerability that many are unwilling or unable to offer. The theatrical contract becomes far more complex; it’s no longer just about believing, but about *doing*. For the illusion to hold, both actor and audience must navigate this delicate space. A skilled immersive performer knows how to make an invitation feel safe, offering multiple levels of engagement and never forcing an interaction that feels threatening.

The creators of these worlds bear a heavy responsibility. As the team at Strange Bird Immersive notes, you cannot train an audience to be as “in-the-moment” as an actor, but you can, and must, “design environments that engender real interaction.” This means building safety, consent, and clear rules into the fabric of the world. A refusal to participate is not a failure of the audience member, but often a data point indicating a failure in design. The experience must provide a “safety net” for the self-conscious, allowing them to remain within the fiction even if they choose a more observational role. Without this, the magic is not only broken for that individual but can also disrupt the flow for those around them.

In the end, successful interactive art understands that the freedom to participate must always be accompanied by the equally respected freedom not to.

Key Takeaways

- Theatrical immersion is a collective, not individual, state that is highly susceptible to ‘attention contagion’ from distractions.

- Your physical location in the theatre (distance and angle) directly programs your emotional and psychological connection to the performance.

- The unspoken elements of theatre—subtext, silence, and physical blocking—are a powerful language that conveys more meaning than dialogue alone.

How to Navigate the Cramped Comfort of Grade-Listed West End Theatres?

London’s West End is a paradox: it houses some of the most spectacular productions in the world within some of the most architecturally challenging venues. Many of these beautiful, Grade-listed theatres were built in the Victorian or Edwardian eras, designed for a different society with different expectations—and different average heights. The resulting experience can be one of “cramped comfort,” where the splendor of the show is juxtaposed with a distinct lack of legroom and narrow seating. This physical discomfort is not a trivial matter; it is a constant, low-level distraction that can actively work against the suspension of disbelief. It is difficult to lose yourself in the magic of Oz when your knees are jammed into the seat in front of you.

And yet, the magic often wins. Despite these challenges, West End theatres attracted a record 17.1 million audience members in 2023, a testament to the enduring power of live performance. The success of a show like *Harry Potter and the Cursed Child* at the Palace Theatre, which has 1,442 seats and one of the steepest balconies in London, illustrates this point perfectly. Patrons are willing to navigate restricted views from support pillars and dizzying heights in exchange for being part of a cultural event. This willingness creates a kind of pre-show contract: the audience implicitly accepts the physical limitations of the venue in anticipation of the artistic reward.

Navigating this environment is a skill. Experienced theatre-goers learn to “read” a seating plan, prioritizing aisle seats for the illusion of extra space or the front row of the Dress Circle for its typically superior legroom. They rely on seat-review websites to avoid the dreaded pillar or safety rail. This preparatory work is part of the modern pilgrimage to the theatre, an acknowledgment that achieving perfect immersion sometimes requires a bit of strategic planning. The physical discomfort becomes a small price to pay for the profound, shared experience that can only happen within these historic walls.

To truly lose yourself in the performance, the first step is to arm yourself with the knowledge to make your physical experience as seamless as possible, allowing the magic on stage to overcome the limitations of your seat.

Frequently Asked Questions About Why Suspension of Disbelief Fails When the Audience is Distracted?

Are West End theatre seats really that cramped?

Yes, many older West End theatres were built before modern seat sizing standards, resulting in cramped legroom. Theatres that haven’t been renovated in 10+ years typically have the most uncomfortable seating.

Which seats offer the best legroom?

Aisle seats and front rows of the dress circle typically offer more legroom. Newer or recently renovated theatres like the Gillian Lynne tend to be more comfortable overall.

How can tall people find comfortable seats?

Check seating reviews before booking, prioritize aisle seats for extra ‘air space,’ and consider stalls or dress circle sections which generally have better spacing than upper levels.